Unlock the power of real assets investing with Sprott’s Masterclass video. Dive into gold, silver, copper and uranium with industry experts Ed Coyne, Ryan McIntyre and Steve Schoffstall as they reveal strategies to navigate global uncertainties and identify opportunities. Discover how to leverage precious metals and critical materials to potentially build a resilient, future-ready portfolio.

For the latest standardized performance and holdings of the Sprott Energy Transition ETFs, please visit the individual website pages: SETM, LITP, URNM, URNJ, COPP, COPJ and NIKL. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Video Transcript

Ed Coyne: Hello, and welcome to Sprott's CE credit video on real assets. For today's video, we'll be covering the value of precious metals with a focus on gold and silver, as well as exploring the opportunities and critical materials such as copper and uranium. My name is Ed Coyne, and I'll be your host today for this 50-minute CE credit class on real assets. I've also asked Ryan McIntyre and Steve Schoffstall to join me today. Ryan is a Managing Partner and Senior Portfolio Manager at Sprott, and Steve is Director of ETF Product Management at Sprott.

I've asked Ryan to address potential ways to help investors allocate to gold and silver in building a diversified portfolio. Then, we'll turn to Steve to cover the mid to long-term outlooks on opportunities in both critical materials, primarily focusing on copper and uranium. With that, let's get started. Ryan, let's start with 2024. 2024 has been a wonderful year in both gold and silver through early November. What in your mind were some of the primary drivers behind that performance?

Gold and Silver

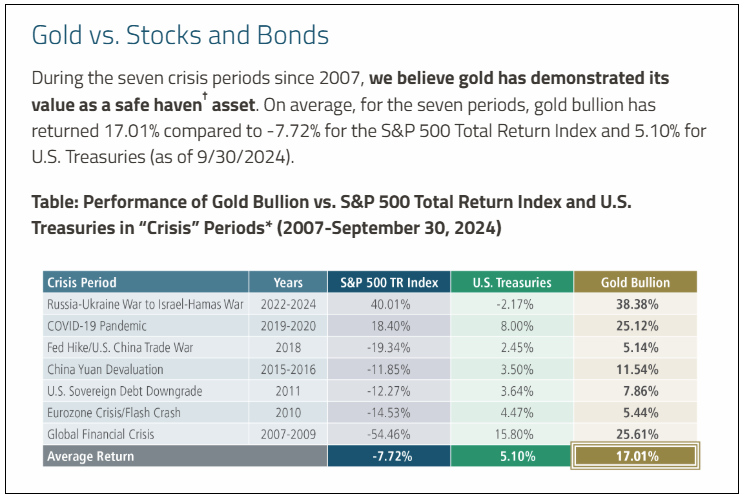

Ryan McIntyre: Gold and silver prices have done well so far in 2024. Silver and gold are both up approximately 30% year to date. And the big drivers, to me, revolve around uncertainty in the world. You've got a lot of uncertainty in the geopolitical environment, whether you're talking about Ukraine and Russia, whether you're talking about things that are going on in the Gaza Strip, or even between China and Russia.

You're seeing many different political divisions expressed through violent actions around the world, which is unsettling to most people. And then there's uncertainty in the economy, right? You've seen a lot of different headwinds, particularly in Western Europe, with manufacturing in the U.S. similarly, although the U.S. continues to plug along pretty well.

I think there's a lot of uncertainty in terms of where the economy is going in terms of direction. And as a consequence of uncertainty, I think you've seen a lot of people start to look at diversifying their portfolio beyond just the standard S&P 500, emerging market or international equities, and standard bond allocations. Gold and silver, I think, really do fit the bill to add some great diversification to a portfolio. And it's, to me, no surprise that people have gone there.

Ed Coyne: We're going to unpack that further, both on the economic side and the geopolitical side, as we go through today's class, but I agree, we're seeing more capital move in this direction. So I'm looking forward to having a further conversation on that. Before we go into that, Steve, let's turn to critical materials for a moment. Both copper and uranium have had similar moves over the last couple of years. What do you attribute those moves to as well?

Copper and Uranium

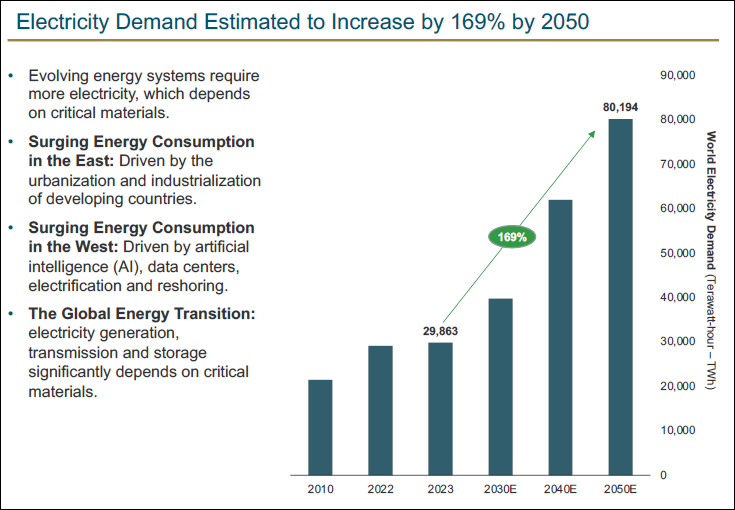

Steve Schoffstall: It really boils down to electricity, right? If you look at where we're at from a global perspective, we've gone through a period where most of the electricity demand was coming from developing nations, such as China, India, and some other developing countries. And we're starting to see now in the U.S. and other Western countries for the first time in a number of years where we're starting to see electricity demand increase. If you were to look at it globally between 2020 and 2050, we expect a 165% [169%] increase in electricity demand. When you step back and take a look at what's driving that, when you start looking at developing nations, their standard of living is starting to increase. India is a great example. About 97% of the households in India have electricity, but only 8% have air conditioning.

Figure 1.

Source: IEA World Energy Outlook 2024 Net Zero Emissions Scenario. Included for illustrative purposes only.

It's a small look at what's happening in developing countries. When you look at the electricity demand more broadly in the developing world, China needs somewhere around 600% more electricity, which is what their demand will be. India around 250%. When you juxtapose that with what we see in Western and more developed countries, it's about technological innovation. The most recent place we're starting to see that play out is in relation to data centers, particularly as they're supportive of artificial intelligence. Those data centers are massively energy-intense endeavors, from running the complex data algorithms to cooling the data centers themselves. What's causing this is a renewed look at our overall energy output. And as that relates to nuclear energy, we're starting to see, particularly as it relates to Silicon Valley, they're starting to embrace nuclear energy in a way that hasn't been the case previously.

One of the things that we look at is firms like Microsoft and Amazon; many of those companies have net-zero emissions targets within their corporate mandates. As they build these data centers, they have to figure out a way to get clean or renewable energy to power them. That's where they're starting to increasingly turn to nuclear energy because it provides reliable base load power and is one of our cleanest energy-generation sources. Just two examples of that are, if you look at Amazon earlier this year, they bought a data center right next to a nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania. And just within the last several weeks, we've also seen Microsoft and their talks with Constellation Energy about restarting the Three Mile Island nuclear reactor in Pennsylvania. Both of those are to power data centers. As we go through the rest of this decade, we expect that to play out, and that's something that we expect to see contribute to the overall energy demand in the West.

Ed Coyne: I believe base load applies to everybody, right? India and China, as they continue to grow, they need a 24/7 power source as well. They don't want their ACs cutting on and off as they get ACs in their house for the first time. I have to believe the base load is the primary theme as it relates to energy.

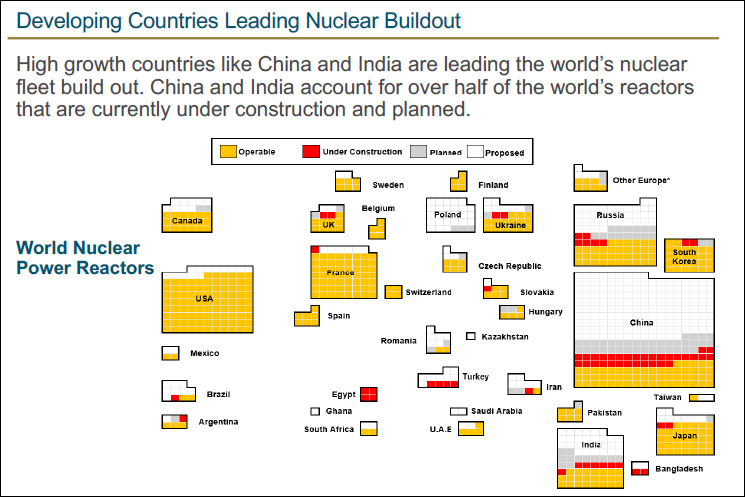

Steve Schoffstall: It is. And when you look at China specifically, if you look at the 440 or so nuclear reactors that are either scheduled to be built or planned to be built, most of those are in China. They're leading the way.

Although the U.S. is the largest nuclear power in the world, China's looking to move into that role. We do see this at certain conferences; if you go back to the COP28 conference in December of last year, we see over 20 nations signing an agreement to triple nuclear energy capacity out through 2050.

Outside that, the UK came out and said, "We're going to quadruple through 2050." That's what their goal is. So we've seen, over the last several decades in the U.S. and the UK and many developed countries, the reliance on nuclear energy has decreased. We're now looking to return to those more historical norms or, in some cases, surpass those norms regarding how much contributes to the overall grid. Our second piece is not just around the energy we need, but it's also transitioning from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources. And with that, we're seeing governments increasingly embrace nuclear energy as that reliable baseload power alternative.

Figure 2.

*Other Europe includes Armenia, Belarus, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Netherlands

Source: World Nuclear Association as of October 30, 2024. Bloomberg: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2024-06-12/uranium-price-surgehelps-deadly-metal-dominate-commodity-market

Ed Coyne: Let’s talk about that for a moment because it seems like the narrative is just getting stronger and stronger. Going back to performance, the last couple of years have been strong, but it seems like a little bit of a pause or increased volatility has come into both the uranium market and, to a lesser extent, the copper market. Can you address that a little bit as well?

Steve Schoffstall: Let's take copper first, then we'll touch on uranium. If you think of the copper market, a lot of that traditionally, since China started being industrialized in the earlier part of this century to a larger extent, was driven by the economy of China. So as China's economy went, too did the price of copper to a large extent. What we're seeing, if you go back to the early part of this century, back to 2000, the price of copper per ton was about $2,000 a ton, consequently that year. Depending on the day, we're now around $9,500 to $10,000 a ton.

We’ve seen a consistent rise in the price of copper. This is in spite of the fact that the Chinese economy is struggling, and they're trying to keep that economy moving along. Their commitment to renewable energy and building out their electrical grid is really helping to support copper as it relates to China. China is the largest buyer of copper, and they've continued to do that as their economy has slowed down. As it relates to nuclear energy, a similar type of narrative over the last 10 years or so. After the last 10 years, when we bottomed in the uranium prices, we've seen them peak at about $106 a pound starting this year. We're now sitting in the high 70s to low 80s.

The uranium market is a bit different from other markets in that much of the uranium purchased is contracted into the future. Most of the activity isn't happening in the spot market, which gives a somewhat different picture of what's happening in the underlying market.

Post Election

Ed Coyne: Great. Thank you. And before we dig a little deeper into gold, silver, copper, and uranium post-election, I think we have to at least comment on the market reaction. And I'd like to hear from both of you regarding post-election; what is your take on gold, silver, copper, and uranium? Has the narrative changed at all? Has it paused? Has it been enhanced?

I want to get a sense of your thoughts from both of you now that the election is behind us and the president-elect, Trump, is coming back into office in 2025. So, Ryan, let's start with you. How should potential investors continue to look at gold and silver now that we have a little bit more clarity, potentially clarity, in the marketplace, at least from a political standpoint?

Ryan McIntyre: We got the question a lot before the election; now we know more about who will be in power and so forth. And I guess the key thing for us is that it doesn't change how we think about gold or silver because we're thinking long-term. And when you're trying to evaluate different circumstances, one of the best things you can do is think about things that aren't likely to change. One of the things that we think is likely not going to change is the fiscal irresponsibility of the U.S. and other Western countries, for that matter.

From our perspective, we're really on the border in terms of the fiscal responsibility now that markets can tolerate. And I think that's one thing that will definitely continue and will be at the forefront in terms of people's minds. However, the one thing consistent with gold or silver is its monetary properties in terms of “protection” against the devaluing of the currency in terms of debasement, printing of money, and so forth. As long as you believe inflation will continue to be positive, gold and silver prices should be very good in the long term. From our perspective, that does not change. The only other aspect that we're going to talk about is the geopolitical framework.

It feels like these divisions are getting wider and wider in terms of the trust factor, I would say, between the Eastern and the Western parts of the world. And I think that is very likely to continue as well, which should also be beneficial for both monetary metals, so gold and silver, just because I think that they'll be used more in the diversification mix of trade investment as a safe haven because I think trust factor is probably, to me, one of the biggest things that's been eroding within the U.S. and external to the U.S. as well. One of the few things that can protect against that, which is completely independent as an asset, is gold and silver, given that they also have monetary properties.

Figure 3.

Ed Coyne: Well said. Steve, we have to talk about this as well. At least on the surface, Trump appears less supportive of the energy transition theme. How do copper and uranium go beyond that current narrative?

Steve Schoffstall: Great question. It's multifaceted, right? Each aspect of the energy transition or the critical materials space can be viewed differently as it will react differently, in our opinion, to the election. So first, if you were to look at things like electric vehicles (EVs), there's a common narrative that the next administration is going to come in heavy on electric vehicles and that we'll see sales drastically drop. That's one of the narratives that's being floated out there.

In actuality, assuming what he said in the past relates to electric vehicles, the Trump administration will likely look for a bottom-up approach regarding EV demand. So, let's get the government to pull back on the mandate side and let the market bear out how the EV train will move forward. With that, we expect to see plug-in hybrids play an increasingly important role as that's a great way to bridge consumers from an all-gasoline-powered car to an all-electric car. You get the plug-in hybrid approach that's very much supportive of critical materials because you'd still need a lot for that battery, a lot of copper, lithium, and nickel, in some cases. If you look at other aspects of the energy transition, another key piece is the drilling aspect related to natural gas, which supports our view.

Over the longer term, we expect to see an all-of-the-above approach as it relates to our energy consumption going forward. That means things like nuclear energy, wind, solar, hydro, and natural gas. We've anticipated that being a part of the energy mix going forward. It's also important to remember that as we sit here today, the House and who controls the House isn't known, and it's likely whichever party controls the House is going to have a very slim margin. It will be difficult for the next administration to come in and make these unilateral changes, even if the Republicans win the House. So that's something we'll have to keep an eye on. Another thing that is very supportive of nuclear energy, in our view, is that if you go back 15 or 20 years, the support for nuclear energy would have largely been a Republican issue.

That's changed a lot over the last three or four years. The Biden administration has put many incentives in place for the nuclear industry and to build our nuclear industry. Those are things that Republicans are still supportive of, and we expect that to carry through to the next part of the administration. And then finally, as it relates to mining, all indications are that the next administration will be very much in favor of on-shoring, that same process that's happened for the last five years or so, where we look to move supply chains away from China and away from other politically sensitive areas. From a mining perspective, we expect those incentives will continue to be there for miners to build out gold and silver mines and our energy and critical materials infrastructure that'll stay here.

One final point as it relates to subsidies: if you were to look at a map of where a lot of these clean factories were built over the last four or five years or where they're expected to be built going through the end of the decade, there's a belt that's started to develop between Michigan down to Georgia. Some refer to it as a battery belt. There are other industries like solar and wind manufacturing. A lot of those are deeply Republican states, and we would expect that representatives and senators from those states wouldn't be so quick to give up the subsidies that are supporting their local economies.

Ed Coyne: That's a great point. And I'm glad you mentioned the word mining because I want to talk a bit about the equity side, the miners themselves. We often talk about physical copper, uranium, gold, and silver; sometimes, I think the miners get overlooked.

Indeed, from a performance standpoint, historically, that's been the case for the last decade or so, but that seems to be changing also. So, Ryan, let's go back to you for a minute and talk about the miners for a second. How should investors think about gold and silver from a diversification standpoint and from an opportunistic standpoint? How should they think about the mining stocks?

Ryan McIntyre: From the equity standpoint, typically, what we're looking for when you're getting to that area is we're looking at it more of a tactical allocation of anywhere between zero and 5%. We think of it like any other sector that you think about and if you try to take advantage of the cycles.

When things are out of favor on the gold equity side or silver equity side, when they're losing money, when they can't raise money, projects aren't proceeding, maybe supplies are stagnating or dropping. Those are situations where you want to get involved and probably allocate to the full 5% and take advantage of those cycles. When you do that, what you're getting, in addition to just exposure to gold or silver, is torque to the metal price through the operational leverage from the firm itself in a couple of different ways. For one, if you were to expect gold price to increase by 10%, we'd expect the profitability of the average gold or silver mining company to increase by about twice that, so about 20%.

And so that's one aspect of it. When you also get the gold price increase, you also tend to get increases in reserves resources. Maybe some opportunities for expansions or new project development weren't anticipated at a lower gold price as well. You do get some value-added pieces as well to the equation. Gold mining equities and silver equities provide a little bit of torque, but they do have a little more risk as well in terms of they're more volatile than the physical commodity itself.

Learn More About Allocating Gold to a Portfolio

Ed Coyne: Steve, I got to believe that's similar as it relates to copper mining companies, uranium mining companies, but anything that maybe stands out that's slightly different in that side of the equation that would stand out from a gold and silver mining stock?

Steve Schoffstall: That's correct. You expect to see that torque as it relates to the miners relative to the underlying commodity. I think one sense where it's different versus maybe a gold and silver allocation is that we tend to see investors allocate to the critical mineral space in the growth sleeve of their portfolio.

Particularly as it relates to uranium miners, a lot of portfolios are underweight if they have any exposure to uranium and mining at all. Those are investors that we see typically allocated to the growth sleeve. There's also an argument to be made to add to the energy sleeve as we're diversifying energy sources away from your typical oil and gas type companies.

We don't necessarily see exposure to uranium in those types of sector allocations. Copper is increasingly becoming not only a base metal but also used in technology and conducting electricity. It's also being used in more forms of energy as it relates to wind farms, solar panels and EVs. That growth allocation is a spot where we're seeing a lot of investors looking to slot that exposure.

Ed Coyne: I also appreciate you bringing that up because that's an important distinction about how investors and advisors should slot these allocations within their portfolio. I know, Ryan; you said that in the bond part of your portfolio, on the physical side, the equities would be more opportunistic. I'm assuming the same would be true for copper and uranium. Would you put that on the diversification side, or would you put that on the energy side as well?

Steve Schoffstall: I think it could have that dual role. Right? It does provide diversification in your portfolio. Given the volatility and the expected growth in the critical materials space, we see people add that to their growth sleeves as well. I think it can fit both as a diversification and growth sleeve.

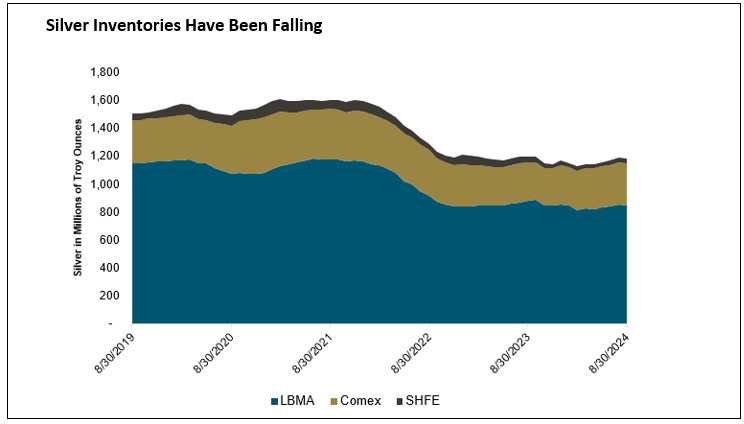

Silver

Ed Coyne: Now, this is a dual question that is coming up. This is silver. Historically, silver has lived within the gold precious metals category, but that seems to be changing slightly. I'm going to start with you, Ryan, first and what have you seen over the last decade as silver has matured? Is it finally stepping out of gold's shadow, or does it still live in that environment or neighborhood?

Ryan McIntyre: I think it'll always live to some extent in part of gold's shadow just because gold is viewed primarily as a monetary element, and silver has got the monetary element as well, but it also has an industrial component in terms of a lot of industrial uses, particularly around electronics and so forth. Silver, I think, does have a great duality to it, and it also attracts a different group of people as well as you'd expect. And what's interesting about silver is the people that it attracts tend to be more economically sensitive to changes in its price. Consequently, if you expect gold to do well, you'd probably expect silver to do even better to some extent just because you tend to get more people coming in to get the extra torque to the gold price.

But then there's also the economic sensitivity around the industrial side of that commodity. And you've seen huge deficits in that commodity over the past several years, anywhere from 15% to 20% of supply, which are huge. From that standpoint, I think there's a lot to be had there as well.

Figure 4.

LBMA represents the London Bullion Market Association, COMEX represents the Commodity Exchange of CME Group, and SHFE represents the Shanghai Futures Exchange. Source: Bloomberg and LBMA as of 8/31/2024. The silver spot price is measured by the Silver Spot USD/Troy Ounce. You cannot invest directly in an index.

Ed Coyne: Steve, can you add to that, as you really spend a lot of time on the critical materials side? Is silver coming up more and more in conversations as we talk about this energy transition, as we talk about critical materials? Are more people and more investors looking at silver as a critical material?

Steve Schoffstall: They are. Ryan said it has that dual role as a precious metal and industrial metal. As it relates to critical materials space, it's increasingly used in photovoltaics with solar panels. So basically, once the solar panels are being produced, there's a silver paste that can get applied to the solar panel, and that will be used to send the electricity throughout the grid. A lot of people don't necessarily, I think appreciate that silver's the most conductive metal that we have out there, even more so than copper.

It's generally cost-prohibitive to use in the same way that copper is. Second, if you were to go back a few years ago, you would see somewhere around eight, maybe 10% of the silver that was mined would be used for solar panels. We're starting to see that percentage increase higher. Now, around 16% or 18% of the silver being produced is expected to be used for solar panels.

Ed Coyne: I want to stay on that for a moment, which is the old supply and demand. It seems like the theme here is supply and demand. We need more of it. We don't have enough of it. What have you seen in the last, say, five years or so change as it relates to supply and demand? I think Ryan, you said earlier that President-elect Trump is coming into office, maybe a little bit more supportive of drilling and so forth here in the U.S. Do you see that supporting the supply-demand dynamics, and how long do you think that will take to catch up from a pricing standpoint?

Ryan McIntyre: There are two parts to the demand and supply side. On the demand side, I think it's obvious that Trump would like to see the economy grow as fast as possible when he's in his presidency. I think from that standpoint, he will do a lot to release the regulations, whether it's drilling in terms of finding new exploration deposits and so forth. I think he will try to take down some of the permitting aspects of it to a more manageable timeline.

Ed Coyne: Not to cut you off, but what are those timelines right now? Just to give a sense to people what we're talking about?

Ryan McIntyre: So right now, to permit of mine, generally speaking, takes about 15 to 20 years, depending on where you are in the world. It causes a lot of cyclicality in this space to a degree because when you look at it from a supply-side perspective, its inability to respond quickly to changes in demand is difficult. They can't start producing more or, even frankly, if there's oversupply, start descaling the mines or shutting them down. It's very tough to influence things higher or lower very quickly.

That’s one of the things you can take advantage of on the investment side when we're talking about materials, whether it's the precious metal side or the other critical materials. But from the supply side, I would expect some inroads to be made that way. But on the other hand, it still takes a long time to build the mine, so that's not going to happen tomorrow either.

Ed Coyne: I have to believe that's the same for copper and uranium mines, but the demand side for particularly uranium, let's talk about that for a moment, has been relatively quiet until recently. Copper, we've always needed copper; we're going to continue to need copper. What has changed in that, and what does that look like from a landscape standpoint as supply is trying to catch up with demand? Can you talk about the timeframe? What are we talking about here?

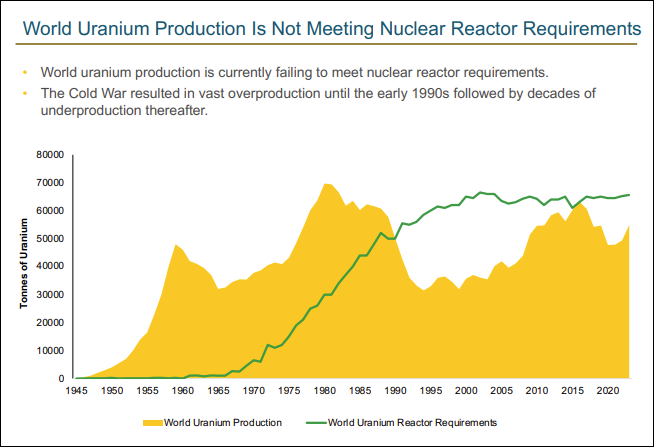

Steve Schoffstall: We take a longer-term view in the way that we look at the critical materials' opportunity. If you were to go back over the last 15 years or so, we did have a lost decade as it relates to investing, particularly in uranium miners. We were able to get away with that because we did have these large secondary stockpiles that had been built up over time so that utilities could draw on those stockpiles. Several years ago, we started to deplete those stockpiles. We're at a point now where we're not producing enough uranium to offset how much is going to be required by utilities. We have many utilities, not so much in the U.S. yet, which tend to be lagging in this space, but they're starting to secure the uranium supplies over the next three to five years or so.

If you were to look at China, they're the only country that's stockpiling uranium in any sort of meaningful way. The U.S. utilities haven't gotten there yet. They're a little bit behind the eight-ball. What this is going to cause, in our view, is that there's going to be this catch-up where we're going to see Western utilities try to catch up and source more uranium. At the same time, we're also contending with these long lead times to get a new mine operational. From a uranium perspective, if you were to go out through about 2040, there's an estimate that we’ll have a cumulative deficit of uranium to meet our needs both now and what's expected for growth between then of somewhere around 1 billion, up to 2 billion pounds depending on what your estimate is as far as net-zero and small modular reactors and advances in technologies as it relates to reactors.

Figure 5.

Source: OECD-NEA/IAEA, World Nuclear Association and UxC LLC as of 12/31/2023. Represents the most up-to-date information available.

On the copper side, we have a somewhat different story. We're right around that parity part where we have demand meeting supply. We expect to see supply fail to keep up with demand over the next decades. A large part of this is, again, getting those new mines up and running. Copper mines, on average, take about 16.5 years to get up and running from discovery to production. But the interesting thing about the copper market is that it's in a position now where, as you said earlier, it is a very common metal. We've mined all the easy copper at this point. Miners are having to dig deeper and go more remote. That requires infrastructure to be built to get these mines from more remote locations.

Since all that easy copper is mined, we will need more investment in the copper space. We're also going to need to see the permitting timelines come down. Another factor that we have as it relates to copper is that a lot of the copper is mined in countries prone to social unrest. We see that in Panama, where we had one of the larger mines, the Cobre Panama copper mine, come offline because of social issues that relate to how much the copper miner is paying back to the government on their royalty. So, hopefully, that's a mine that they'll get worked out and figured out. But we still do have this overhang of needing to find more copper and needing it to be in a meaningful supply to meet demand.

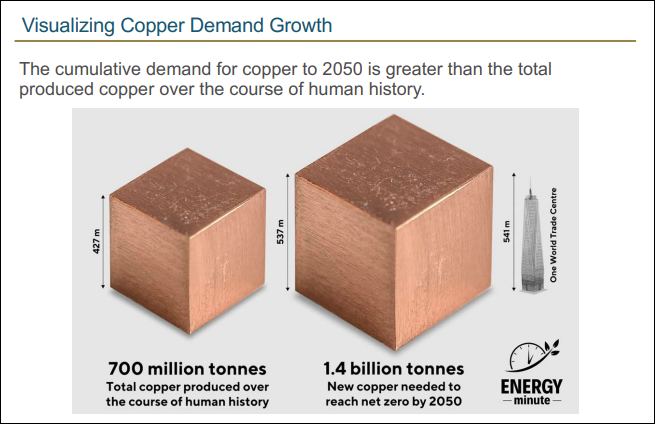

Figure 6.

Sources: ENERGYminute. https://energyminute.ca/infographics/the-volume-of-2050-net-zero-copper-demand/

Ed Coyne: It sounds to me that it's a multi-market cycle opportunity, both on the gold and silver front as it relates to supply and demand and certainly on the copper and uranium front. This is not one market cycle opportunity. This seems like a multi-market cycle, multi-decade opportunity from an investment standpoint.

Ryan McIntyre: I think you also have climate change in there as well. You've seen increasing incidents due to climate change preventing mines from producing or halting them temporarily. And so, to me, that's a huge factor. That's a huge tailwind as well for pricing in the sector. You've got yields kind of going down, so the intensity required for each new pound of copper or ounce of gold or ounce of silver is going up. And then you also have climate change as well. So those are two big tailwinds that you've got for this space.

Ed Coyne: So you basically have to do more to get less.

Ryan McIntyre: You got it.

Ed Coyne: So the price has to go higher.

Ryan McIntyre: Absolutely.

Ed Coyne: Not that we're promising, but we're just saying that's the opportunity. I want to go back in time a little bit and talk about history for a moment because I think for a newer investor going into this space, having a historical reference to what's happened in the last couple of decades might be important. From the early seventies, we saw several bull and bear markets specifically as it related to gold, and, I guess, as a byproduct, silver as well. Can you talk about the environment in the 1990s bear market and the 2000s bull market and compare that to where we are now in the cycle?

Ryan McIntyre: Yes. I'll start off in terms of gold in terms of 1971, because that's really the key moment for gold when it became basically liberated. We went off the gold standard in the U.S. in 1971. The gold price was approximately $35 an ounce. And over the next decade, so throughout the 1970s, you had significant inflation, you had political crises and uncertainty around the world. The oil crisis would probably be the one that stands out in most people's minds. You had rates and gold prices go up significantly. Gold went up from $35 an ounce, and it peaked at around $850 an ounce in around 1980. As a consequence, Volcker obviously raised rates significantly to encourage people to slow down on the inflation side and get their mentality into a different mindset than before.

That took a while, but he was successful. Over the next two decades, from 1980 through to 2000, you basically had sort of a steady decline of gold for the first decade, and then you had it basically level off and ended up being just sub $300 an ounce in and around 2000. And then from that point on, gold took off for the next decade. So it went from about 2000 to about $1,800 an ounce. I think largely due to a few financial crises, but more importantly, I think you had a change in monetary behavior from a lot of the central banks around the world. And I think really what that's done is that's caused, I would say, a looser feeling around the fiscal responsibility that governments have about the money that they print and create.

From that standpoint, gold was really elevated to that next level. From 2011 where it peaked around that $1,800 level, you saw it decline down to about $1,200 an ounce or so temporarily in about 2015. And then again, ever since then, it's gone back up. And we just touched off $2,800 and ever since the recent U.S. elections, backed off now to about $2,600. And again, I think one of the things that's been at the forefront of that is monetary extremism. And I think people are forgetting that the governments are using the people's own money to spend. And I think people forget that they view the government as a separate entity, independent of themselves, but I think people should remember it's their own money. And being fiscally irresponsible as a government is probably going to come back to haunt us at some point. But it’s a great way to play that is the two monetary metals that we've been talking about, gold and silver if you want some antidote to what the central banks have been doing and the governments and the fiscal side as well. We'll see how it goes, but those are two great ways to take advantage of that.

Ed Coyne: Awesome. Thank you. And Steve, I know you touched on this briefly about uranium, and there’s a lot of supply, but that's really all been consumed, and now we need to get new supply online. Same with copper. Talk a little bit more about copper, though. You touched on this, about how copper has traditionally been tethered to the Chinese economy because they consume; correct me if I'm wrong, but over 50% of all copper consumption comes out of China. That seems to be changing as well. Can you talk a little bit about how that came to be, and where do you think we're going if you look forward to both supply and demand of copper and uranium?

Steve Schoffstall: Starting with copper, if you were to look at a price graph of the price of copper, I think I mentioned earlier that around the turn of the century, it was about $2,000 per ton. You would see a ramp up going through the industrialization of China in the early 2010s, and then we saw a kind of pullback a little bit. Today we're up around $9,200-$9,300 a ton, I believe, is where prices were this morning.

The important thing to remember about copper is, and as we talked about its decoupling a little bit from the Chinese economy, is that if you were to plot it from 2000 out to where we are today, there are ebbs and flows, the price, but consistently it’s been trending higher. And that’s what we like to see in areas of the commodity market where we think we’re into that bull phase. We do see those higher highs, and we’re not seeing lower lows. We do see corrections, which we think are helpful. But the trend has been much higher.

Similar to the uranium space, we saw the same thing going back to the early part of the 2010s, we saw the price of uranium peak around $140 a pound or so. From there, part of the commodity supercycle kind of pulled back. We saw prices come down to about 20 or $25 a pound. Recently at the start of this year and over the last four or five years, we’ve seen prices really come back to where we topped out around $106. That’s come down somewhat. We’re now around $77 -$78 a pound. Again, we view that as a healthy correction. Many of the uranium transactions we see don't take place in the spot market. When we look at the prices that the uranium miners are contracting out, we're starting to see contracting prices in that on the upper side, the $120 to $130 a pound. So that would suggest to us that the uranium market and uranium prices are continuing to move higher, and that's something we foresee going into the next decades with healthy corrections throughout.

Ed Coyne: And that would be what you refer to as sort of spot market and term market. Just for those who maybe don't understand that part of the ecosystem, can you talk a little bit about the term market a little further? What's taking shape in there right now? What are these energy companies looking to do?

Steve Schoffstall: The easiest way to understand the term market is to think of the spot market. The spot market is if you wanted to go out and buy uranium today, that's the current spot price. When these uranium miners and utilities run into off-take agreements where the utilities buy material from the miners, they'll go into the contract (term) market. And typically what they'll do, they'll buy material, it could be a year in two, three, four, up to five years or even longer in advance that they're looking to secure material. With that, there's usually a cap and a floor. What we're seeing with the caps are now up around $120, $130 in some cases per pound. Floors are above what we're seeing in the current spot market. And there's this kind of push and pull that we're seeing now where the miners understand where prices are moving. And in our opinion, many U.S. utilities are a little behind the eight-ball in securing that future supply. They're looking at the spot price and saying, well, the spot price is around $80. Why are you having an upper level in your contract price at $130?

We think at some point we're going to see these U.S. utilities needing to enter the market and that's going to be supportive of higher prices both in the spot and term market. What we really see in the spot market is occasionally, we'll see miners that maybe didn't get the amount of uranium out of the ground that they needed to fulfill their contracted prices. Sometimes they'll come into the spot market and buy material, so they have that for delivery. But we're seeing that contracting is where the significant price moves are happening at the moment.

Ed Coyne: I'd like to talk about gold and silver, copper and uranium as a pure investment. I think so often, people have seen all these metals from a consumer standpoint. I consume copper in my home, and maybe I participate in uranium through how I pay for my energy and gold and silver, typically from a jewelry standpoint potentially. Consumers may know these metals, but they haven't really thought of them as investments.

Let's circle back for a moment and discuss a way to think about gold and silver purely from an investment standpoint, whether you're a direct investor or an advisor.

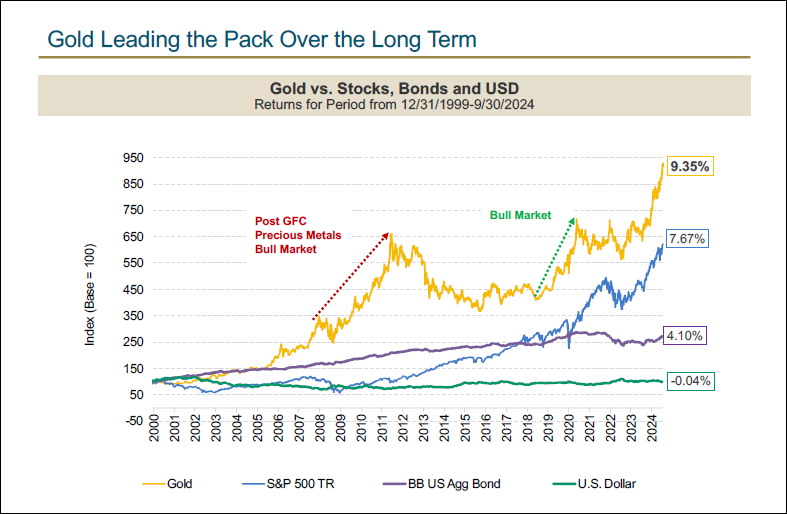

Ryan McIntyre: If you look at gold price since it's gone off the gold standard in 1971, it's compounded at about 8% a year. Which to me is a very good return considering the properties that it has. One of the unique properties that gold has is that it really adds a lot of diversification to one's portfolio, given that it's really uncorrelated with a lot of the other asset classes that people typically invest in. It's actually a real enhancer on the risk-return spectrum for people's portfolios. When things are doing well in your portfolio, it could be that gold might be a slight offset or vice versa, which is really handy. So you don't get these extreme moves in your portfolio. So that's typically a great thing to have.

Figure 7.

Source: Bloomberg. Period from 12/31/1999-9/30/2024. Gold is measured by GOLDS Comdty Spot Price; S&P 500 TR is measured by the SPX; US Agg Bond Index is measured by the Bloomberg Barclays US Agg Total Return Value Unhedged USD (LBUSTRUU Index); and the U.S. Dollar is measured by DXY Curncy. You cannot invest directly in an index. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The second aspect is that gold volatility alone is much lower than most other asset classes, which people are surprised to hear. People often think about commodities and how cyclical they are and the dramatic moves, but gold's a bit unique in the sense that it actually has much lower volatility than a lot of the other asset classes, whether it's U.S. equities, international equities, or emerging market equities. It's a very good lower-volatility play in that regard.

Silver brings in the industrial component as well. It has similar monetary components as gold, but it also has an industrial side. It moves a little bit more with the economic cycle of the economy, and so, as you’d expect, you get more volatility with silver.

Ed Coyne: Great, thank you. And Steve, again, a similar question, speaking to the advisor or the direct investor. I know we already talked a little bit about this as far as how to think about both copper and uranium, but as you're looking to allocate dollars to this space, what would you like to leave the investors or the advisors with when they're allocating capital for their investors? What would you like to leave them with as they think about these assets?

Steve Schoffstall: The first thing that we provide through our exchange-traded fund (ETF) lineup is optionality. We have seven critical materials, ETFs. We have a broader-based Sprott Critical Materials ETF (SETM), which is kind of our broad-based product. It provides exposure to up to nine different critical materials. That's one where investors that might not fully have a view on one critical material over the other might look to allocate to SETM.

From there, we allow investors to really take a targeted approach. We have LITP, which is our Sprott Lithium Miners ETF, which provides pure-play exposure to lithium miners. One of the differences in our lithium product versus others you might see out there is that we don't have those downstream exposures that you would see. There are no EVs in our lithium product. It's all mining and production-based. We also have the Sprott Nickel Miners ETF, which is the only nickel miners ETF on the market, ticker NIKL.

And then as it relates to the copper side, we have two copper ETFs. The Sprott Copper Miners ETF (COPP) is our all-cap copper product. And then also the Sprott Junior Copper ETF (COPJ) which is the only ETF to allow investors to make a view based on junior mining companies in the copper space. And then, as it relates to uranium, again, we have ticker URNM, which is Sprott Uranium Miners ETF. Ticker URNJ, our Sprott Junior Uranium Miners ETF, targets just those junior uranium mining companies. Again, that's the only ETF of its kind.

What these all have in common is that they all have pure-play targeted exposure. We go through great pains when developing a product to go through with the index providers to really come up with a process that is really targeting those companies that get at least 50% of their revenue or assets from the underlying commodity. As investors are looking to make decisions, we want to provide funds so that, for example, if you want to make a decision about investing in copper, you know you're investing in copper miners.

One of the things that often gets lost in this space, and copper is a great example of this. If you look at the 10 largest copper miners in the world, only four of those are publicly traded and majority copper companies. So only those four would be eligible in our COPP index (Nasdaq Sprott Copper Miners™ Index or NSCOPP™), whereas other funds might have copper miners where maybe only 15% or 20% of the exposure is related to mining copper. So that's kind of the key differentiator amongst our products as it relates across the suite.

So as investors are looking to make those tactical allocations into the growth sleeve or energy sleeve, that's the point we would have that conversation and talk through what pure-play means and why that's beneficial. Typically, we see over longer terms that the stocks outperform on the upside. Now, you will expect underperformance on the downside. So, as the spot market's moving down, you would expect that underperformance. Still, it gives that level of leverage that we discussed earlier, and we think that plays well across growth sleeves and many investor portfolios.

Ed Coyne: Ryan, let's go back to an advisor's or investor's approach to allocation. What are some ways at Sprott you guys can expose clients to both the physical and the equity markets?

Ryan McIntyre: The great part about Sprott is that we've got products for every aspect of the natural resources space. And as it relates to precious metals, we've got two great products on the physical side. We have the symbol PHYS, our physical gold trust, Sprott Physical Gold Trust, and PSLV, which is our physical silver trust, the Sprott Physical Silver Trust. The great thing about those two products is that they are completely allocated to physical material, so physical gold and physical silver are allocated to us. And we charge a very low fee for that as well. And so it is cost-effective in terms of owning physical gold and silver versus storing it at home, which is hard to get insurance for physical gold and silver in your home. It's a very easy way and effective way to do it. And the other aspect is from the gold and silver mining perspectives.

Ed Coyne: So how about on the equity side? How can you get allocation to the equity side?

Ryan McIntyre: On the equity side, we've got a couple of different ways. We've got a mutual fund called the Sprott Gold Equity Mutual Fund. And the other one is the Sprott Gold Miners ETF (SGDM). There’s an active approach with our mutual fund. We've got a great team who's executing on that. But if you also want a passive approach using a factors-based approach, which is what we use, I would recommend our ETF as well, SGDM.

Ed Coyne: And let's go back to the physical side for a moment. You talked about being fully allocated and owning the precious metals. In your mind, why is that important relative to getting exposure in the general market?

Ryan McIntyre: Well, I think two things. You wouldn't like to get exposure to anything you didn't think was going to get a good return over time. And the second part of that is diversification. It really optimizes your risk-return allocation for your portfolio by you're either trying to enhance return while lowering risk. It really is a nice addition to the portfolio. And to me, one of the things that really helps people stay invested over time and stay the course of their long-term strategy is to really have an all-weather portfolio. Adding gold into the mix dampens the volatility. And it probably helps people's psyche in terms of staying the course, in terms of maintaining their investment program.

Ed Coyne: And to go back to the miners for a moment, people are used to thinking about equities as large-cap liquid equities and more opportunistic small-cap equities. In the mining world, we call them seniors and juniors. Can you talk a bit about their personalities, what a senior miner looks like, without naming names, and what a junior miner looks like, and then talk about the respective opportunities in both? Where do you see potential opportunities as an equity investor?

Ryan McIntyre: Sure. I'll start with the whole spectrum of investing in the gold sector. The least volatile and least risky is physical gold. And then you start moving into the mining categories where you start introducing a little bit more risk. It really goes to the spectrum from the largest senior producers who are established gold-producing companies, good balance sheets, good access to capital, good engineering teams, and so forth. Then you go all the way down to the junior end of the scale, which is the much riskier end of the scale but also an area where you can add a lot of value through exploration or development. And so really, I would say a lot of the key value-add in this space is either finding a new discovery or enhancing a discovery with exploration. And then it's really transitioning that exploration success to a producing asset through the development process.

And that's the other category where they can add a lot of value is developing an undeveloped mine into an actual mine. And so, to me, I think it's actually good to have broad exposure across the categories because you've got more stability, I would say, with the senior producers. But with the junior side, you often get value-add in addition to the gold or silver price, whether it's a polymetallic mine. And so to me, having broad exposure across is probably the best allocation for that category.

Ed Coyne: Steve, let's shift back to critical materials in general and talk a little bit about historically, even at Sprott, how the opportunity has evolved over time, going from simply electric vehicles all the way into the globalization of the electric grid. Can you talk a bit about that and how that's really evolved and how investors should be looking at this opportunity longer term?

Steve Schoffstall: I can even go back a little further than that. I remember being in middle school in the 1990s and looking and learning in my earth science class about solar-powered cars and how that was the way of the future.

Ed Coyne: Okay.

Steve Schoffstall: Where we sit today, we're not at solar-powered cars, but what we are at is solar power powering our cars, just not on the car itself. We do have EVs now that are very much involved in our daily lives. But even if you look at the last several years as the critical materials space is starting to mature, even though it's still in the early stages of what we believe to be a bull market, is you see five or six years ago, a lot of it was aspirational. A lot of, "We'd like to do this. We'd like to have net-zero carbon by 2050."

Where we sit today, now we're starting to see those pledges that are signed by over a hundred countries around the globe to decarbonize and have those net-zero decarbonization pledges, many to 2050, some after that, some a little bit before. But we've also seen that as pledges can go, anybody can make a pledge. It's not worth the paper it's written on.

Ed Coyne: Right.

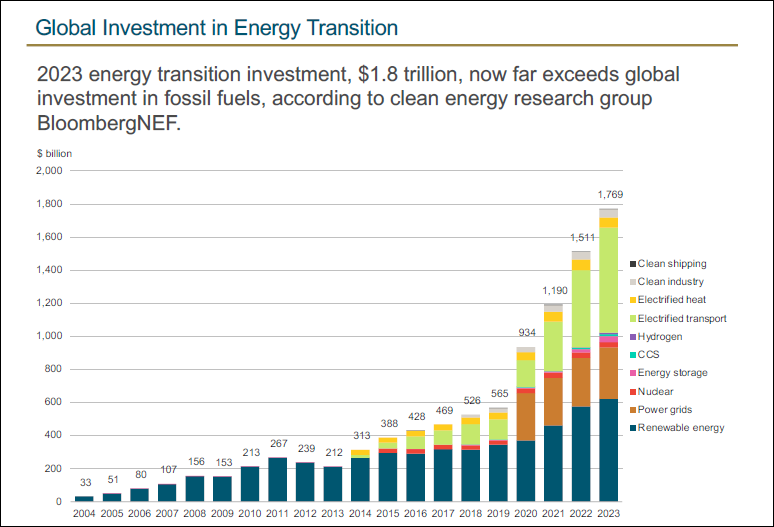

Steve Schoffstall: The investment that we're seeing come into that. If we look at last year alone, BNEF, the Bloomberg New Energy Finance, estimates that about $1.8 trillion was spent on the energy transition. We've seen significant growth over the last five or six years in that space where two years ago the investment in the energy transition space equaled that of fossil fuels, and now we're past that and expect that to be into the future. And even since we launched our lineup, we've seen a shift from critical materials and their role in the energy transition has really broadened now into, based on what we're seeing with the AI and storage facilities that we discussed earlier, that we really need more electricity. It's not just about clean energy. It's about we need more energy.

Figure 8.

Source: BNEF Energy Transition Investment Trends 2024.

Ed Coyne: Right.

Steve Schoffstall: With that, we've seen greater importance being placed not just on the energy transition, but we have to meet the energy needs of the globe now. Eastern countries and developing countries are requiring massive amounts of energy. And so I'd say that's probably been the biggest change we've seen in the last several years: that mindset of it's all about the energy transition, and then we're seeing that funding come through and push us a little closer to those aspirational goals.

Ed Coyne: It seems to me also that I think the initial narrative was one versus the other. And I think you said earlier that we really need all of it. We need a base flow, we need alternative energies, we need traditional energy sources. Anything on that horizon that you think from a technology standpoint may be changing? What should investors be looking at as they go forward, and what should they be paying attention to as it relates to critical materials?

Steve Schoffstall: It really falls into all of the above approaches. Now you have oil companies that are mining lithium and experimenting with that because they see the need for and the potential for EVs and lithium extraction. That's a place where they're investing quite heavily in different ways to extract lithium. When you look at the nuclear energy space where we're moving away from these large nuclear reactors and toward smaller modular reactors that can be built off-site, really, and assembled maybe in a more remote location, they're much smaller, can be used for things like data centers. They could be used to at one point, power mines, mining operations and the infrastructure that goes along with that. The ability to have these small modular reactors is getting a lot of attention, particularly in the U.S. And I think that's why you don't see the U.S. announcing nuclear projects at the same rate that we see in China, for example, is because we're getting close to that technology becoming commercially viable.

And that's really the path forward here, I believe, in the U.S., is that modular reactor type approach. And one of the benefits is you could take an old coal plant, remove the infrastructure, and then put a modular reactor in its place. Now, you're generating nuclear power and using the infrastructure already in place to transmit that energy.

Ed Coyne: Interesting.

Steve Schoffstall: So that's where we're really starting to see, as it relates to the generation side of power, those are some of the changes that we're seeing over the next, call it, decade or so.

Ed Coyne: That's what I was going to ask you. From an expectation standpoint, what is a realistic expectation of seeing small modular reactors become viable and enter the economy? What's the timeframe for that?

Steve Schoffstall: 2030 is a spot that most people point to as nuclear energy becoming a reality. And there's a lot of funding flowing into this space. Bill Gates is committing a lot of funding to the modular reactor design. We see Silicon Valley. We talked about data centers and how they're looking to use nuclear energy. They're very much in tune with what's going on in that space and would likely use that type of technology. But I think we'll start to see those roll out and become more commonplace in the next decade or so.

Ed Coyne: And not to throw water on aspirational targets like 2050, but from a realistic standpoint, we talk about supply-demand dynamics. How realistic are we going to get to a carbon-neutral future by 2050? What needs to happen for that to even get close to happening?

Steve Schoffstall: I think you would have to upend world economies for that to happen, which might bode well for things like gold and silver, but you do have to have a goal to work toward. If 2050 is that goal, it's a nice round number that we can work toward those aspirational goals. That's great. I think that the key thing is flexibility. Right? We understand that we're in the early stages here, we believe, and technology's changing. The material that we're bringing out of the ground, the quantities that we need to have, just to be able to reach those 2050 goals in and of itself is a huge lift. To give you a frame of reference, if you look at all the copper that we've ever mined before 2022, it would be about half of what we have to mine between 2022 and 2050.

Ed Coyne: And you say ever, you mean ever.

Steve Schoffstall: Ever.

Ed Coyne: We’ve got a way to go then. I think that highlights the supply-demand dynamics and the long-term investment opportunity, both in copper and uranium and as well in gold and silver. As we continue expanding our economy, as more people allocate capital and an invested portfolio, we talk about electricity. Still, we don't talk about, hey, as the economy grows, so does wealth and people want to diversify their portfolios. It seems to me that both copper and uranium and gold and silver have a bright future.

Steve Schoffstall: I think just one last thing on the mining aspect, and as it relates to building infrastructure, a lot of mines are outside of population centers. They're fairly remote. Those types of operations will likely continue to use fossil fuels to power those operations. Then we're moving to, there's a movement toward getting more solar power to power generators or wind farms to power generators and get some electric vehicles in there. In our view, fossil fuels aren't going away anytime soon. It's too ingrained in our economy.

Ed Coyne: I think that's a great point to end: It's not one or the other. It's all of the above. Well, thank you both for your time.

Investment Risks and Other Important Information

Product-Specific Disclosures

The Sprott Gold Equity Fund (the “Fund”) invests in gold and other precious metals, which involves additional risks, such as the possibility for substantial price fluctuations over a short period of time; the market for gold/precious metals is relatively limited; the sources of gold/precious metals are concentrated in countries that have the potential for instability; and the market for gold/precious metals is unregulated. The Fund may also invest in foreign securities, which are subject to other risks including: differences in accounting methods; the value of foreign currencies may decline relative to the U.S. dollar; a foreign government may expropriate the Fund’s assets; and political, social or economic instability in a foreign country in which the Fund invests may cause the value of the Fund’s investments to decline. The Fund is non-diversified, meaning it may concentrate its assets in fewer individual holdings than a diversified fund. Therefore, the Fund is more exposed to individual stock volatility than a diversified fund.

Investors should carefully consider investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses. This and other important information is contained in the fund prospectus which should be considered carefully before investing. To obtain a prospectus please visit www.sprott.com or call 888.622.1813.

NOT FDIC INSURED • MAY LOSE VALUE • NOT BANK GUARANTEED

Sprott Asset Management USA, Inc. is the investment adviser to the Fund. The information contained herein does not constitute an offer or solicitation by anyone in the United States or in any other jurisdiction in which such an offer or solicitation is not authorized or to any person to whom it is unlawful to make such an offer or solicitation. Sprott Global Resource Investments Ltd. is the Fund’s distributor.

The Sprott Funds Trust is made up of the following ETFs (“Funds”): Sprott Gold Miners ETF (SGDM), Sprott Junior Gold Miners ETF (SGDJ), Sprott Critical Materials ETF (SETM), Sprott Uranium Miners ETF (URNM), Sprott Junior Uranium Miners ETF (URNJ), Sprott Copper Miners ETF (COPP), Sprott Junior Copper Miners ETF (COPJ), Sprott Lithium Miners ETF (LITP) and Sprott Nickel Miners ETF (NIKL).

Before investing, you should consider each Fund’s investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses. Each Fund’s prospectus contains this and other information about the Fund and should be read carefully before investing. A prospectus can be obtained by calling 888.622.1813 or by clicking these links: Sprott Gold Miners ETF Prospectus, Sprott Junior Gold Miners ETF Prospectus, Sprott Critical Materials ETF Prospectus, Sprott Uranium Miners ETF Prospectus, Sprott Junior Uranium Miners ETF Prospectus, Sprott Copper Miners ETF Prospectus, Sprott Junior Copper Miners ETF Prospectus, Sprott Lithium Miners ETF Prospectus, and Sprott Nickel Miners ETF Prospectus.

The Funds are not suitable for all investors. There are risks involved with investing in ETFs, including the loss of money. The Funds are non-diversified and can invest a greater portion of assets in securities of individual issuers than a diversified fund. As a result, changes in the market value of a single investment could cause greater fluctuations in share price than would occur in a diversified fund.

Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) are bought and sold through exchange trading at market price (not NAV) and are not individually redeemed from the Fund. Shares may trade at a premium or discount to their NAV in the secondary market. Brokerage commissions will reduce returns. "Authorized participants" may trade directly with the Fund, typically in blocks of 10,000 shares.

Funds that emphasize investments in small/mid-cap companies will generally experience greater price volatility. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of experiencing investment losses. ETFs are considered to have continuous liquidity because they allow for an individual to trade throughout the day. A higher portfolio turnover rate may indicate higher transaction costs and may result in higher taxes when Fund shares are held in a taxable account. These costs, which are not reflected in annual fund operating expenses, affect the Fund’s performance.

Sprott Asset Management USA, Inc. is the Investment Adviser to the Sprott ETFs. ALPS Distributors, Inc. is the Distributor for the Sprott ETFs and is a registered broker-dealer and FINRA Member.

Sprott Physical Gold Trust and Sprott Physical Silver Trust (the “Trusts”) are closed-end funds established under the laws of the Province of Ontario in Canada. The Trusts are available to U.S. investors by way of a listing on the NYSE Arca pursuant to the U.S. Securities Exchange Act of 1934. The Trusts are not registered as investment companies under the U.S. Investment Company Act of 1940.

The Trusts are generally exposed to the multiple risks that have been identified and described in the prospectuses. Please refer to each prospectus for a description of these risks. Relative to other sectors, precious metals and natural resources investments have higher headline risk and are more sensitive to changes in economic data, political or regulatory events, and underlying commodity price fluctuations. Risks related to extraction, storage and liquidity should also be considered.

Gold and precious metals are referred to with terms of art like store of value, safe haven and safe asset. These terms should not be construed to guarantee any form of investment safety. While “safe” assets like gold, Treasuries, money market funds and cash generally do not carry a high risk of loss relative to other asset classes, any asset may lose value, which may involve the complete loss of invested principal.

All data is in U.S. dollars unless otherwise noted.

Sprott Asset Management LP is the investment manager to the Trusts. Important information about the Trusts, including the investment objectives and strategies, applicable management fees, and expenses, is contained each Trust’s prospectus. Please read the prospectus carefully before investing. You will usually pay brokerage fees to your dealer if you purchase or sell units of the Trust on the Toronto Stock Exchange (“TSX”) or the New York Stock Exchange (“NYSE”). If the units are purchased or sold on the TSX or the NYSE, investors may pay more than the current net asset value when buying units of the Trust and may receive less than the current net asset value when selling them. Investment funds are not guaranteed, their values change frequently, and past performance may not be repeated. The information contained herein does not constitute an offer or solicitation to anyone in the United States or in any other jurisdiction in which such an offer or solicitation is not authorized.

Relative to other sectors, precious metals and natural resources investments have higher headline risk and are more sensitive to changes in economic data, political or regulatory events, and underlying commodity price fluctuations. Risks related to extraction, storage, and liquidity should also be considered.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. You cannot invest directly in an index.

Investments, commentary, and opinions are unique and may not be reflective of any other Sprott entity or affiliate. Forward-looking language should not be construed as predictive. While third-party sources are believed to be reliable, Sprott makes no guarantee as to their accuracy or timeliness. This information does not constitute an offer or solicitation and may not be relied upon or considered to be the rendering of tax, legal, accounting, or professional advice.

Defined Terms

Inflation and currency devaluation “protection” implies a potential investment hedge against certain market environments and in no way indicates protection against risk of loss, including total loss of invested principal.

The term “pure play” relates directly to the total universe of investable, publicly listed securities in the investment strategy. The spot market is a public financial market where commodities are traded for immediate delivery where the term market involves contracts that continue for a longer duration.

Risk-return spectrum refers to the relationship between the amount of potential return to be gained on an investment and the amount of risk undertaken in that investment. Theoretically, as the risk increases, so would the potential return. References to risk-return metrics do not guarantee or imply any particular investment outcome, and past performance is no indication of future results.

A supercycle refers to an extended period of economic growth, driven by various factors, but characterized by increased demand for commodities and higher asset prices, often lasting several years (or decades).

Nasdaq Sprott Copper Miners™ Index (NSCOPP™) is designed to track the performance of a selection of global securities in the copper industry, including copper producers, developers and explorers.

Nasdaq®, Nasdaq Copper Miners™ Index, and NSCOPP™ are registered trademarks of Nasdaq, Inc. (which with its affiliates is referred to as the “Corporations”) and are licensed for use by Sprott Asset Management LP. The Product(s) have not been passed on by the Corporations as to their legality or suitability. The Product(s) are not issued, endorsed, sold, or promoted by the Corporations. THE CORPORATIONS MAKE NO WARRANTIES AND BEAR NO LIABILITY WITH RESPECT TO THE PRODUCT(S).

®Registered trademark of Sprott Inc. 2024